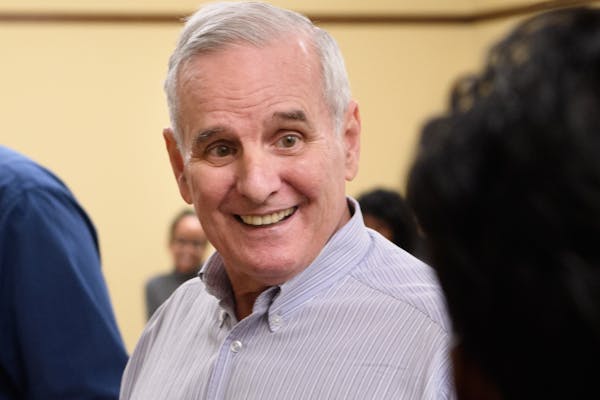

One thing hasn't changed over the past two decades as prostate cancer has stricken public figures such as New York Mayor Rudi Giuliani, U.S. Sen. John Kerry, and now Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton: Patients don't know whether to get screened, and doctors often don't know what to do when they find cancer.

Those uncertainties were reflected by the spike in calls to Minnesota clinics following Dayton's disclosure last month that he has prostate cancer, and his announcement Monday that he would have it surgically removed.

"I've gotten a lot of patients calling who are like, 'Uh-oh, am I due for my PSA?' " said Dr. Jocelyn Rieder, a urologist at Park Nicollet in St. Louis Park.

Despite extensive research over the years, medical groups have come to different conclusions on whether to routinely offer PSA blood tests that can indicate the presence of prostate cancer, and whether to treat any cancer that is found with surgery or radiation — or to do nothing at all.

Even the most ambitious and comprehensive study to date, published late last year, couldn't clarify the best course. Following 1,600 men with low-risk prostate cancer over 10 years, researchers in the Protect trial found no difference in death rates, regardless of whether men treated their cancers with surgery or radiation or left them alone — although untreated cancers were more likely to spread.

Rieder said the consensus is to intervene for prostate cancer patients with life expectancies of 10 years or more, but acknowledged the ambiguities. "Prostate cancer, by all means, is not black and white," she said.

In the case of the 70-year-old governor, Dayton opted for surgery that will take place March 2 at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester. Dayton anticipates resuming his full schedule four days later.

'We were overtreating'

The dilemmas over prostate cancer emerged with the development of the PSA blood test, first approved in the United States in 1994 for screening men who don't show symptoms. While PSA testing has been credited for the decline in U.S. prostate cancer deaths — the death rate had been rising until 1994 — it also has been criticized for the high rate of false positives, which often led men to have biopsy procedures when they didn't have cancer.

In addition, autopsy research has found slow-growing prostate cancers in as many as 60 percent of men 80 and older who died of other causes — indicating to doctors that at least some of their living patients had prostate cancers that never needed to be found or removed.

"We were essentially overtreating," Rieder said. Her Park Nicollet urology group has reduced surgeries and increased "active surveillance" to monitor patients until their cancers grow or cause symptoms.

Screening has declined as well, largely due to a 2012 recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force against routine PSA testing. The task force found too many cases where men without cancer were subjected to the risks of biopsies, and that men with low-risk cancers were subjected to surgeries that come with the risks of incontinence and sexual dysfunction.

Other organizations have taken more moderate approaches. The American Cancer Society recommends that physicians at least discuss screening with men in their 40s who are at high risk due to family histories, and those in their 50s with average risk.

But the net result has been a decline in new prostate cancer cases, from 240,000 in the U.S. in 2012 to an estimated 160,000 this year, according to the Cancer Society.

There is some evidence suggesting the pendulum has swung too far, and that the reduction in testing has resulted in more men being diagnosed late, when their cancers are more aggressive or have spread beyond the prostate, said Dr. Badrinath Konety, a urologic surgeon at the University of Minnesota Medical Center. "These are just early indications," he said. "We need to wait to see if these trends pan out … I don't want to be alarmist."

However, Konety said, the U.S. task force is reviewing its PSA policy this year and might switch to a stance that favors testing in certain situations.

Robotic surgery

New secondary blood tests and MRI imaging scans are poised to improve the detection of cancers in the prostate that require treatment, Konety said. Still, there's the dilemma of which treatment to pursue.

An increase in surgical prostate removals coincided with the development of a new medical device, the da Vinci robotic surgery console, which magnifies vision for surgeons and allows them to make precise movements with surgical tools to avoid damaging the nerves that regulate bladder control and sexual function.

Studies have differed over whether robotic surgery results in fewer of these complications, but agreed that robotic surgery at least results in shorter hospital stays and less blood loss than open surgeries. Most medical centers in the Twin Cities now have these systems, though critics have questioned whether the "medical arms race" to buy them inflated the use of surgery for prostate cancer.

Radiation oncologists say they were encouraged by the recent Protect trial results that found no difference between surgery or radiation, because they believe urologists often overlook radiation as an option.

Dr. Elizabeth Cameron, a HealthEast radiation oncologist, said radiation offers less chance of sexual dysfunction immediately after treatment than surgery. However, some men need the psychological assurance that comes from a prostate removal, which also comes with faster recovery.

"When a man wakes up from his procedure, there's that psychological feeling that it's out," she said.

Personally, Cameron has a different spin. Even if Protect didn't hold up one option over others, it showed that all are decent options.

"Really, a man can pretty much choose whatever feels right to him," she said, "knowing all these options and knowing that he's going to do well."

Jeremy Olson • 612-673-7744

Marijuana's path to legality in Minnesota: A timeline

U.S. Steel won't get exception to pollution rules that protect wild rice, MPCA says

Taste of Minnesota to be enjoyed on the ground and in the air this year

Ex-Hennepin sheriff paid for drunk-driving damages with workers' comp