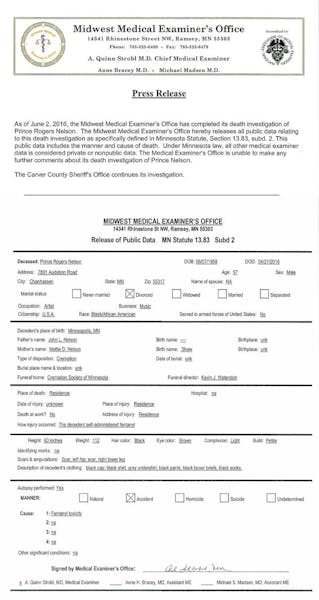

Prince died from an accidental, self-administered overdose of the powerful drug fentanyl, the Midwest Medical Examiner's Office said in a report released Thursday.

The report gave no indication of how Prince obtained the painkiller, nor did it list any other cause of death or "significant conditions."

The 57-year-old musician was pronounced dead the morning of April 21, one day before he was scheduled to meet with a California doctor in an attempt to shed an opioid addiction. Two of his staff members — longtime friend Kirk Johnson and personal assistant Meron Bekure — found his body in a Paisley Park elevator about 9:40 a.m.

Sources told the Star Tribune in the days after Prince's death that a joint state and federal criminal investigation has focused on his use of painkillers and how he obtained them.

Carver County Chief Deputy Jason Kamerud said Thursday that he has "no idea what the time frame is" for completing that investigation. He said the medical examiner's report is simply "a piece of the puzzle."

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is 100 times more powerful than morphine. Administered by injection, lozenge or patch to treat severe pain after surgery and to manage chronic pain, the controlled substance is commonly sold illegally and misused by addicts.

Whether fentanyl had been prescribed to Prince is unclear; the drug is considered highly potent and addictive and is prescribed to patients who have become tolerant of other opioids for pain relief.

The report released Thursday said the 5-foot-3 Prince weighed 112 pounds at the time of death. It also disclosed that he had a scar on his left hip and on the lower part of his right leg. Prince was reported to have had surgery several years ago on an ailing hip caused by years of jumping off speakers while performing in high heels.

When he was found, he was dressed in a black cap, black shirt, gray undershirt, black pants and black socks.

The day before he was found dead, Prince was treated by a Twin Cities doctor for withdrawal symptoms from opioid addiction. The physician, Dr. Michael Todd Schulenberg, a family practitioner, treated Prince for fatigue, anemia and concerns about opiate withdrawal.

Schulenberg did not prescribe opioids to Prince, a source has said.

The doctor gave a statement to a Carver County detective shortly after Prince's death, but has had no further questions from investigators, his attorney, Amy Conners, said Thursday.

Red flag in Moline

Prince died less than a week after his private plane made an emergency, middle-of-the-night landing in Moline, Ill., so he could be treated for a suspected opioid overdose following a pair of performances in Atlanta, sources told the Star Tribune.

Emergency responders arrived at his Paisley Park complex in Chanhassen the morning of April 21 within five minutes of receiving a 911 call, but it was too late. A responding paramedic told staff members, law enforcement officers and others at the scene that Prince appeared to have been dead for at least six hours before his body was found.

The painkiller Percocet also was present in Prince's body when he was found dead, a source familiar with the investigation told the Star Tribune last month.

The medical examiner's report made no reference to that drug.

Sources have said that shortly before Prince's death, members of the artist's inner circle became so concerned about his health that they reached out to Phaedra Ellis-Lamkins, a well-known environmental and labor activist in the San Francisco Bay Area credited with helping Prince recover the rights to his early songs from Warner Bros. She has declined to comment, citing Prince's concern for his privacy.

The night of April 20, less than 12 hours before Prince's body was found, Ellis-Lamkins called Dr. Howard Kornfeld, a pain and addiction specialist in Mill Valley, Calif., seeking his help to get the musician off prescription painkillers, sources said.

Kornfeld could not clear his schedule to immediately travel to Minnesota, so he dispatched his son, Andrew, a pre-med student who worked with his father. Andrew Kornfeld was to meet with Prince and a second Minnesota doctor who is certified to prescribe an opioid addiction treatment medication that Howard Kornfeld uses.

That Minnesota doctor, who hasn't been publicly identified, had cleared his calendar for the morning of April 21 so that Prince could go to his office for an independent evaluation, the source said.

Prince died before the meeting could take place.

Minneapolis attorney William Mauzy, who represents Andrew Kornfeld and has spoken on behalf of Kornfeld's father, said Thursday that neither Kornfeld provided medication to Prince.

"Based on media reports suggesting Prince died at least six hours before Andrew arrived at Paisley Park and the medical examiner's conclusion, released today, that Prince died after he self-administered the extremely potent opioid fentanyl, it is abundantly clear that Andrew and Dr. Kornfeld had nothing to do with Prince's death," Mauzy said. "Andrew and Dr. Kornfeld were simply trying to help, and remain saddened by his death."

'Incredibly potent'

Deaths related to fentanyl have been rising in Minnesota, along with deaths from prescription opioids such as oxycodone and illicit versions such as heroin.

There were 35 deaths related to fentanyl in Minnesota last year, compared with one in 2000, according to death certificate data from the Minnesota Department of Health.

Fentanyl is as addictive and more potent than oxycodone and other opioids, said Dr. Anne Pylkas, a HealthPartners addiction medicine specialist who wasn't involved in Prince's care. Misuse often occurs when patients use two or three 72-hour patches instead of one.

"It's much stronger than morphine, so it's easier to overdose on," Pylkas said, "because it's incredibly potent. We measure it in micrograms, not in milligrams" like other pain relievers.

While autopsies typically conclude within three to six weeks, experts said there are many reasons why Prince's death might have taken longer than usual to investigate.

Deaths associated with drugs slow the investigative process, because they require toxicology tests, then Olympic-level verification to determine the exact type and amount of drugs, said Fred Apple, medical director of the clinical laboratories at the Hennepin County Medical Center, which did not conduct the Prince toxicology testing. Investigators then need to discuss if the level of drugs was toxic enough to have played a role in the death or if it was typical for someone taking medication.

"It's not like you see on TV on 'NCIS,' " Apple said, "where someone shoots something into an instrument and two minutes later, a result comes out."

As news of the medical examiner's findings spread Thursday, a former Prince insider expressed disbelief.

"I'm extremely upset and saddened," Matt Fink, who played keyboard in Prince's band from 1978 through 1990, said in a phone interview.

Meanwhile, the scene at Paisley Park was quiet Thursday afternoon. About 20 fans gathered at a fence where hundreds of mementos had been placed in the hours and days after Prince's death six weeks ago.

A team of volunteers cleaned up the site about two weeks ago, but paintings, flowers, balloons and other memorabilia have since reappeared.

Staff Writers Jon Bream, Dan Browning, Pam Louwagie and Emma Nelson contributed to this report.

david.chanen@startribune.com 612-673-4465

jeremy.olson@startribune.com

612-673-7744

Participant, studio behind 'Spotlight,' 'An Inconvenient Truth,' shutters after 20 years

ABBA, Blondie, and the Notorious B.I.G. enter the National Recording Registry

Dr. Martens shares plunge to record low after weak US revenue outlook