(Note to readers: In today's Hall of Fame vote by the Baseball Writers' Association of America, no candidate gained enough votes to be elected. Read more here.)

* * *

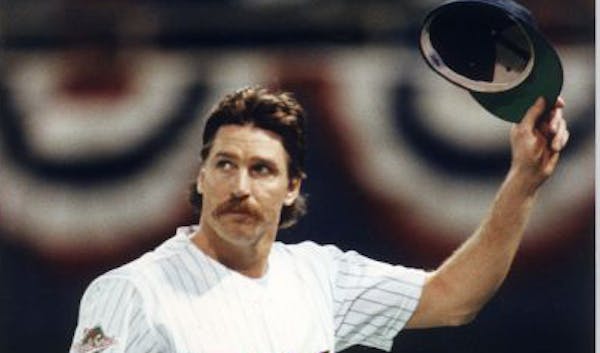

The gates of Cooperstown will not open this year for Roger Clemens or Barry Bonds, two players who -- whatever their sins -- obviously put up numbers worthy of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Of course, the reason they were denied entry is that both men, as well as several other worthy candidates who didn't make the grade, have been linked to performance-enhancing drugs.

Specifically, they violated Rule 5 of the Hall of Fame's election requirements, the "character clause," a self-important criterion that should have been stripped from the ballot decades ago. According to this clause, votes for induction to the Hall must be based not only on a player's record and ability, but also on "integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played."

This is ridiculous. The almost 600 members of the Baseball Writers' Association of America who are responsible for deciding who's worthy of baseball immortality -- or a made-to-order $2,000 bronze plaque, anyway -- should be instructed to confine themselves to metrics that can be measured and compared.

How did Rule 5 come to be? After all, it would have been just as easy to create clear statistical markers to ensure that the best players of their era weren't left out. But that was never the point of the Hall of Fame.

Tourist Trap

It's tempting to think of the Hall as being as timeless and inevitable as baseball itself. Surely our national pastime needed a trusted entity to guard its sacred history.

In fact, as Zev Chafets chronicled in "Cooperstown Confidential," the Hall was basically conceived as a tourist attraction. When it opened in 1939, its purpose was to draw people to an otherwise unremarkable village in upstate New York that claimed to be the birthplace of the game. What better way to do so than to exalt baseball, to weave it seamlessly into the history of the region and our nation?

As for the drafting of the rules for admission, we're not exactly talking about the Constitutional Convention. The Baseball Hall of Fame had two framers: The Hall's founding father, Stephen Clark, a Cooperstown aristocrat who wasn't much of a baseball fan, and Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the game's self- righteous commissioner who levied lifetime bans against eight members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox -- after they'd all been exonerated of criminal charges related to the fixing of the World Series.

("Regardless of the verdict of juries, baseball is entirely competent to protect itself against crooks, both inside and outside the game," said Landis, a former federal judge.)

These two conservative, moralizing men were the prime movers behind Rule 5. Landis, in particular, hoped it would help ensure the election of Harvard Eddie Grant, a passable third baseman who was killed in action in World War I -- and the exclusion of Shoeless Joe Jackson, a member of the 1919 Black Sox and one of the greatest hitters in the history of the game.

We can blame the clause for the ever-thickening fog of mythology that has since enveloped the Hall, turning ex- ballplayers into moral exemplars and puffing up a sports museum into a holy American institution.

In truth, the Hall is representative of America only in as much as it, too, has its share of unreconstructed racists, wife- beaters, drug dealers and sociopaths.

"Wake up the echoes at the Hall of Fame and you will find that baseball's immortals were a rowdy and raucous group of men who would climb down off their plaques and go rampaging through Cooperstown, taking spoils, like the Third Army busting through Germany," former team owner Bill Veeck once said.

Just Whims

Whatever Clark and Landis may have envisioned, the annual Hall of Fame election has never been anything more than a reflection of the whims of voting sportswriters and a group of former players and executives, known as the Veterans Committee.

Yet through it all, the character clause has endured -- a single, smug sentence calling the Hall to some higher purpose than identifying and honoring the game's greatest players.

Think of it less as a clause than a club, one wielded selectively to beat back such undesirables as Shoeless Joe -- who hit .375 in the World Series he allegedly helped throw -- as well as the mouthy Dick Allen and the game's all-time hits leader, Pete Rose.

Now it's being used to beat back not only confirmed but also suspected users of PEDs, which is to say just about everyone who has played professional baseball in the last 20 years.

This is not an optimal situation. At this rate, a generation of baseball fans is going to walk the 5,000-square- foot plaque gallery at Cooperstown straining to recognize a single cast-bronze face.

A simple solution is at hand. The Clark heir who has inherited control of the Hall of Fame, noted equestrian Jane Forbes Clark, could stop protecting her grandfather's character clause like a precious family heirloom and call for it to be deleted from next year's ballot.

My guess is that most writers would welcome the development. They can't be comfortable playing the role of moral arbiters, especially in such a murky realm.

We're never going to know who used what when, or how much it helped them. How can we justify punishing virtually everyone who played during the Steroid Era on the basis of an almost 70-year-old rule that was a bad idea from the start?

What we can say with certainty is that Cooperstown is already something of a Potemkin Village. The longer the character clause continues to exist -- keeping dominant players like Bonds and Clemens out of the Hall -- the further the place is going to drift from reality.

* * *

Jonathan Mahler is a sports columnist for Bloomberg View. He is the author of the best-selling "Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx Is Burning," "The Challenge," and "Death Comes to Happy Valley."

Lab-grown beef is red meat for the conservative base